The Flamingo Lake on the central island of Turkana. Although the water is too alkaline to drink or give to animals, the lake provides fish for the community.

Men of the Gabra tribe are working in a well in Sabarei, located near the border of Ethiopia and Kenya. This traditional well provides water for livestock, but the water is not safe for human consumption. Despite the contaminated water, men pass water in a bucket from hand to hand while chanting.

The northeast shore of Lake Turkana near a fishing village is littered with plastic bags, bottles, and other garbage. The expansion of the fishing industry has brought both economic growth and new challenges to the community.

Three Samburu men are drinking rainwater from a roadside ditch after they escaped from being besieged by a group of local militias on the road to Baragoi.

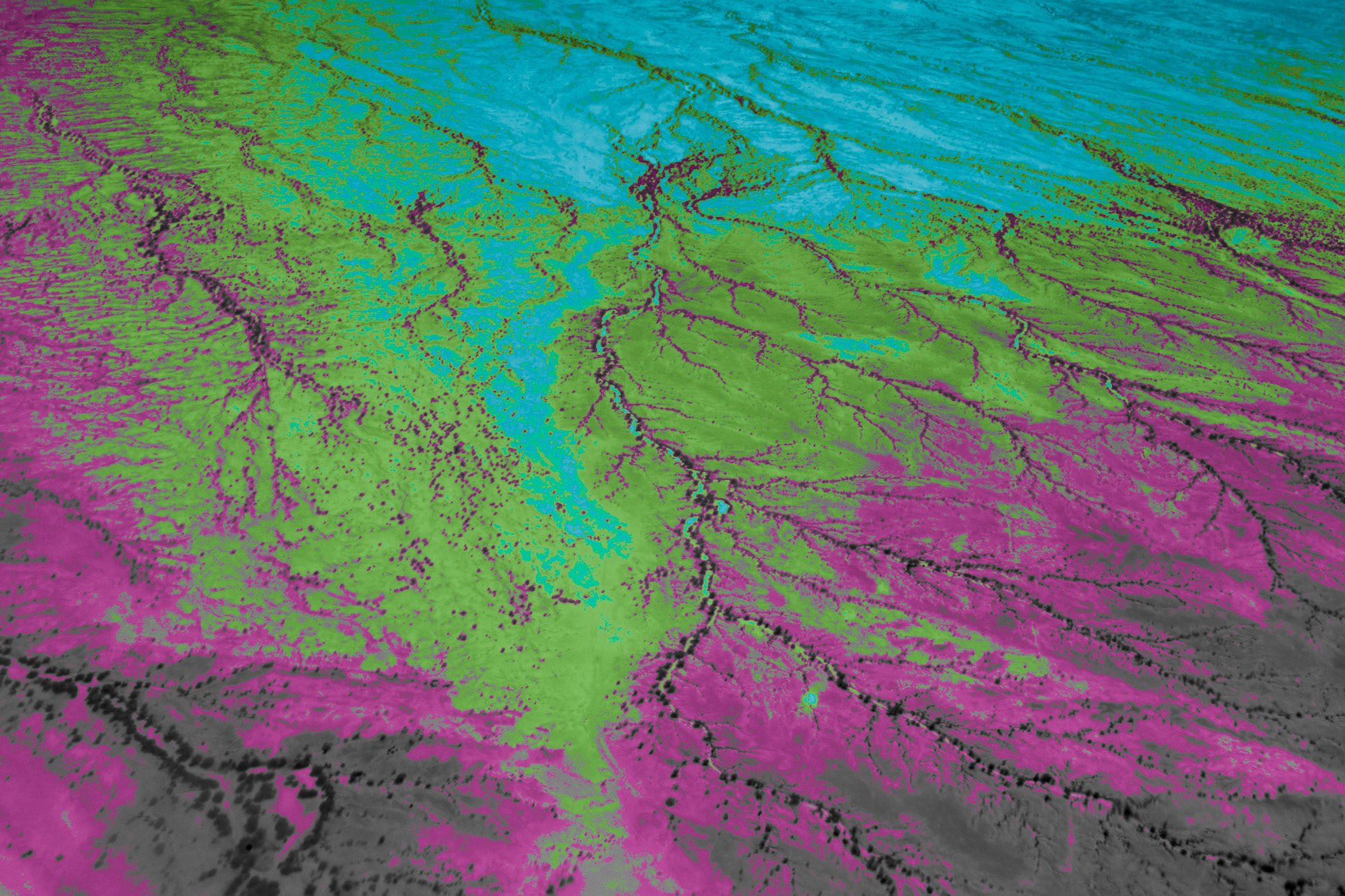

Turkana landscape seen from an airplane above.

Near Loibor Seder, a camel is grazing after a long day walk. The journey and lack of food and water has caused the camel to significantly lose weight.

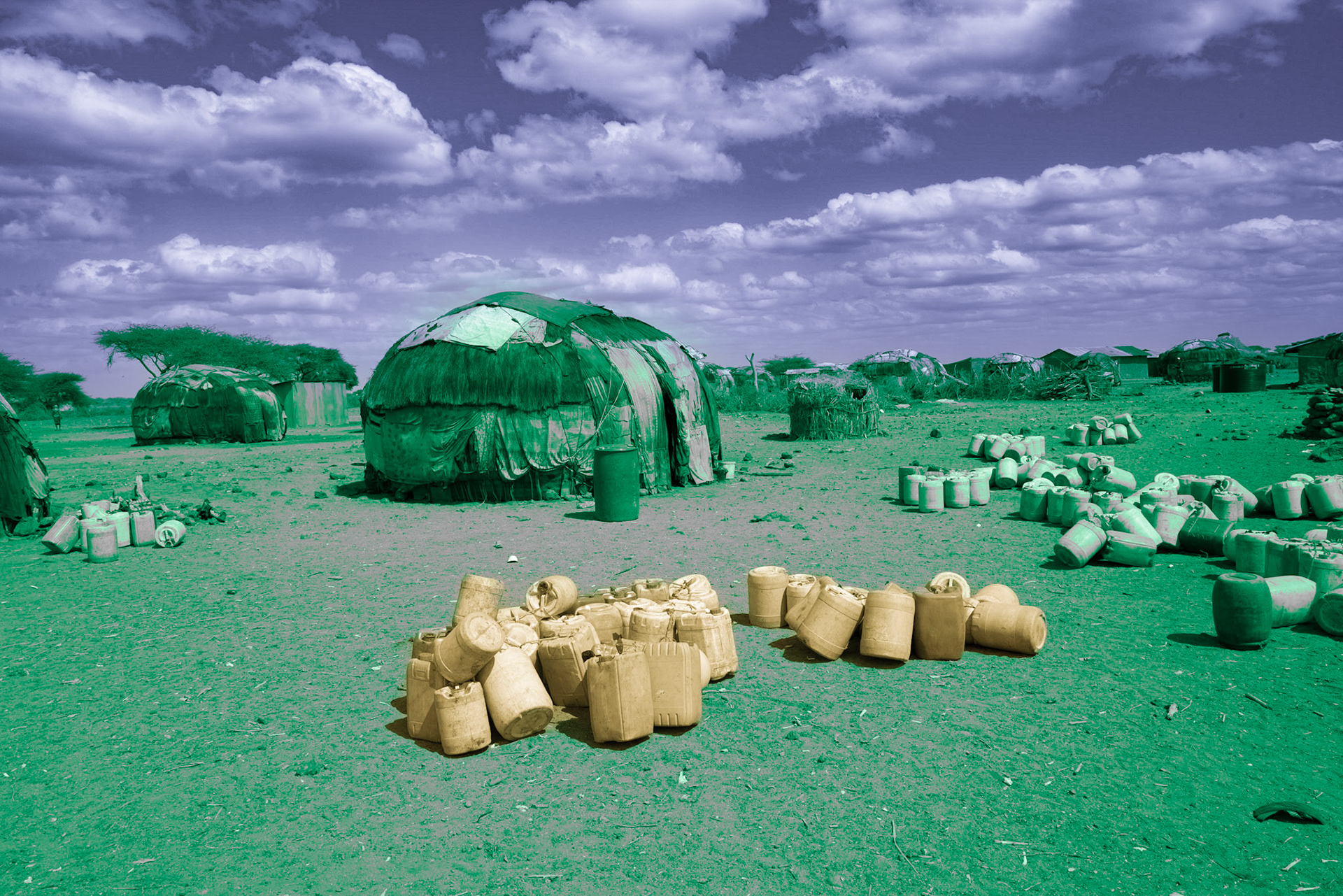

There are numerous empty jerrycans scattered outside a traditional Gabra hut in the village of Forolle, near the Kenya-Ethiopia border. In 2019, 11 people were killed in the area over a dispute on a watering point. Local conflicts, including arms trafficking and cattle rustling, are common in Marsabit county in Kenya.

A deserted settlement in North Horr, previously inhabited by pastoralist communities.

Three Samburu Moran(warriors) armed with G3 rifles are standing along the road from Suiyian to Baragoi. A week ago, three other Samburu were killed by Turkana in this area. The conflict between Samburu, Turkana and other neighboring communities has been escalating.

A woman from the Daasanach community stands near a group of deceased cows at the northern tip of Lake Turkana. Historically, the Daasanach have been pastoralists. Those who have lost their livestock and livelihoods are referred to as the "Dies," or lower class, and now rely on hunting crocodiles and fishing to survive on the lake's shores.

In Maikona, a village located in the north of Chalbi Desert, people are dancing and praying in a church. The pastoralist community in Maikona relies on the seasonal river nearby for their livelihood, but due to the prolonged drought, they have experienced extreme hardship. Many have lost their animals, and even the last group of camels had to leave in search of food in 2022.

The sky is overcast with dark clouds above a deserted roadblock on the Archer's post-Baragoi road in Suiyian. It had been eight months since Suiyian has seen any rain.

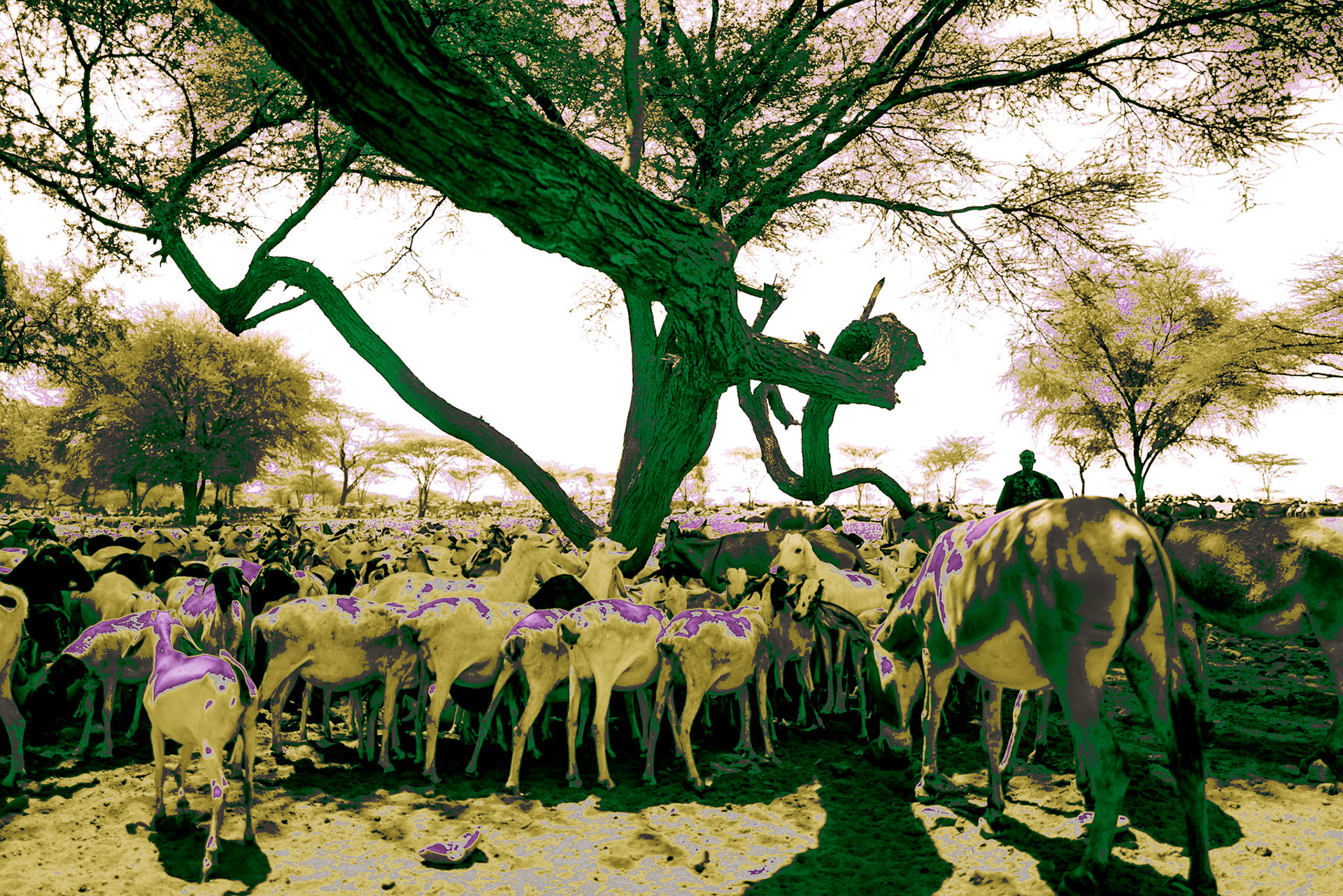

In the dried riverbed of Balesa, a Gabra man and his goats are taking shelter under an acacia tree. He has been traveling with his animals for days heading to Dukana in Marsabit County. Dukana is the only place in the region that has received little rain in recent months.

A Daasanach woman is heading towards her dwelling in the village of Ileret, with the door adorned with various campaign posters in the lead-up to the general elections in Kenya.

A Daasanach man in Selicho is drinking blood from a slaughtered camel. In the traditional diet of pastoralist communities, blood is a valuable source of nutrients and is typically consumed whenever an animal is slaughtered.

In Maikona, the young daughter of a local pastor is taking Amol syrup to treat her fever. The availability of medicine and medical facilities is limited in the remote village. The full extent of COVID-19's impact on the area is currently unknown.

A Gabra woman is filling 1L water bottles with petroleum to sell to BodaBoda (motorcycle) drivers in Dukana. BodaBodas are the primary mode of transportation in the region and are used to transport people and goods. There are no gas stations in these villages.

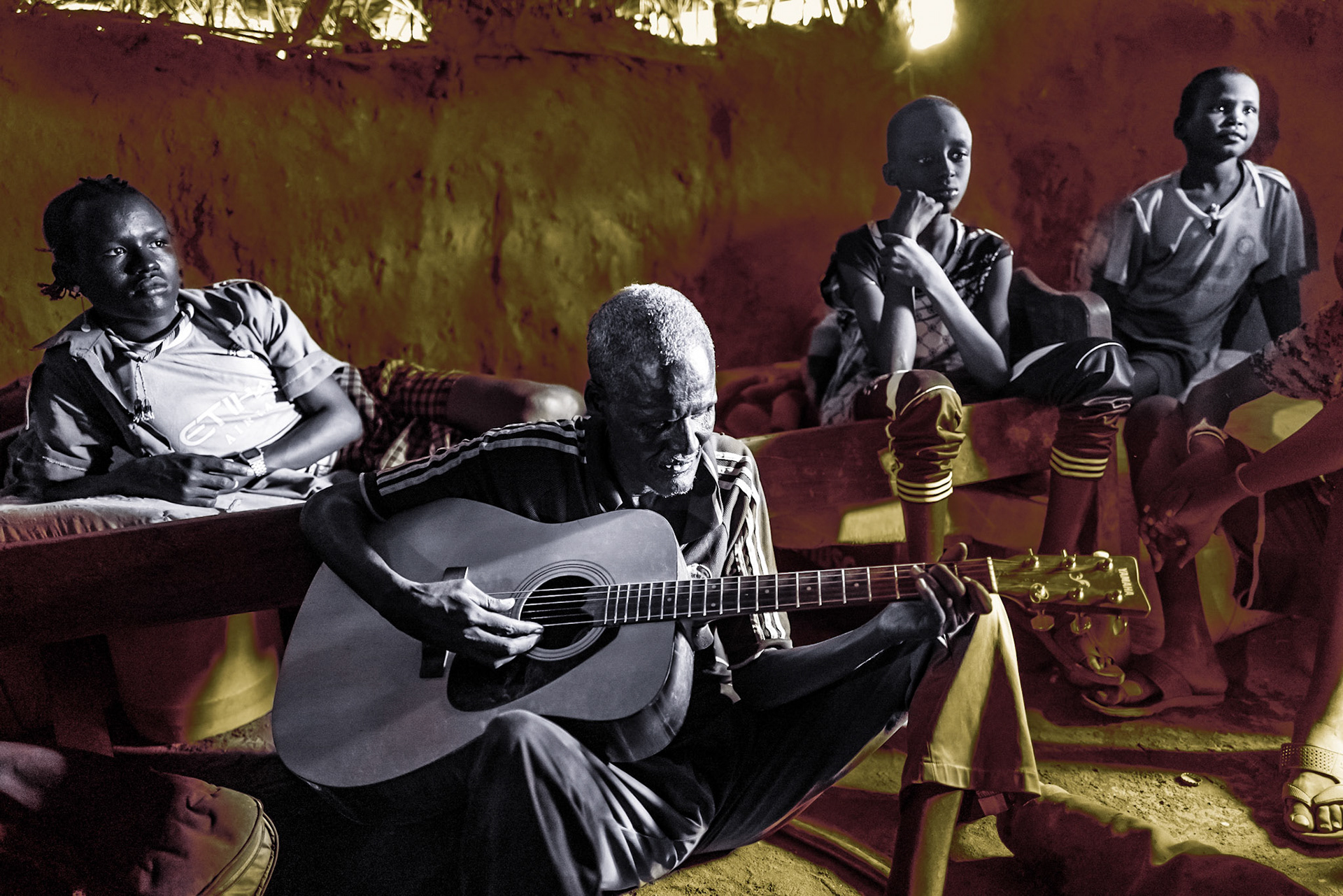

A man is playing a local song in a traditional mud hut in Selicho. While being blind by birth, he learned how to play the guitar in the local church. As the region develops, many indigenous groups like the Daasanach are adopting a more western lifestyle.

The Lake Turkana Wind Power (LTWP) project, in Turkana, is the largest of its kind in East Africa, but has faced backlash from indigenous communities and local residents. The effects of the project on the local population are mixed, with both positive and negative impacts, including the loss of land for the local community, being reported.

A South Sudanese refugee walks in the newly constructed Kalobeyei Settlement, built to accommodate the influx of refugees in Kenya. In September 2016, the number of South Sudanese refugees in neighboring countries exceeded one million, including over 185,000 who fled due to violence in Juba in July 2016. The settlement was constructed in response to the overflow of refugees in the Kakuma camp.

A father from the Democratic Republic of Congo sits with his baby born in a refugee camp, in front of their mud hut in Kakuma.

A mother holds her baby while studying in a classroom in Kakuma refugee camp. The camp has 52 schools offering early childhood, primary, and secondary education. Some of the teachers at the camp are refugees themselves.

A Daasanach mother is nursing her baby inside a hut made of iron sheets and wooden sticks. The region is experiencing a major disaster due to both armed conflict and a severe drought, which has caused crop failures and livestock deaths, leading to the worst famine in East Africa in decades.

Turkana people are selling firewood in Kakuma refugee camp. While the camp provides economic opportunities for the local Turkana community, the increasing population has also put pressure on the already arid land.

A Turkana woman draws water from a dry riverbed in Tarach. Unlike the refugees in the camp, many indigenous communities do not have access to clean water provided by the international community.

An El Molo woman stands on the shore of Lake Turkana in El Molo Bay. The El Molo are a small indigenous tribe in Kenya, with a population of 1,104 according to the 2019 census. Many El Molo people have forgotten their own language and adopted the traditions of the Samburu. Historically, the El Molo were the only major fishing group in the area, but in recent years, people from pastoralist groups such as the Turkana and Rendille also tarted fishing.

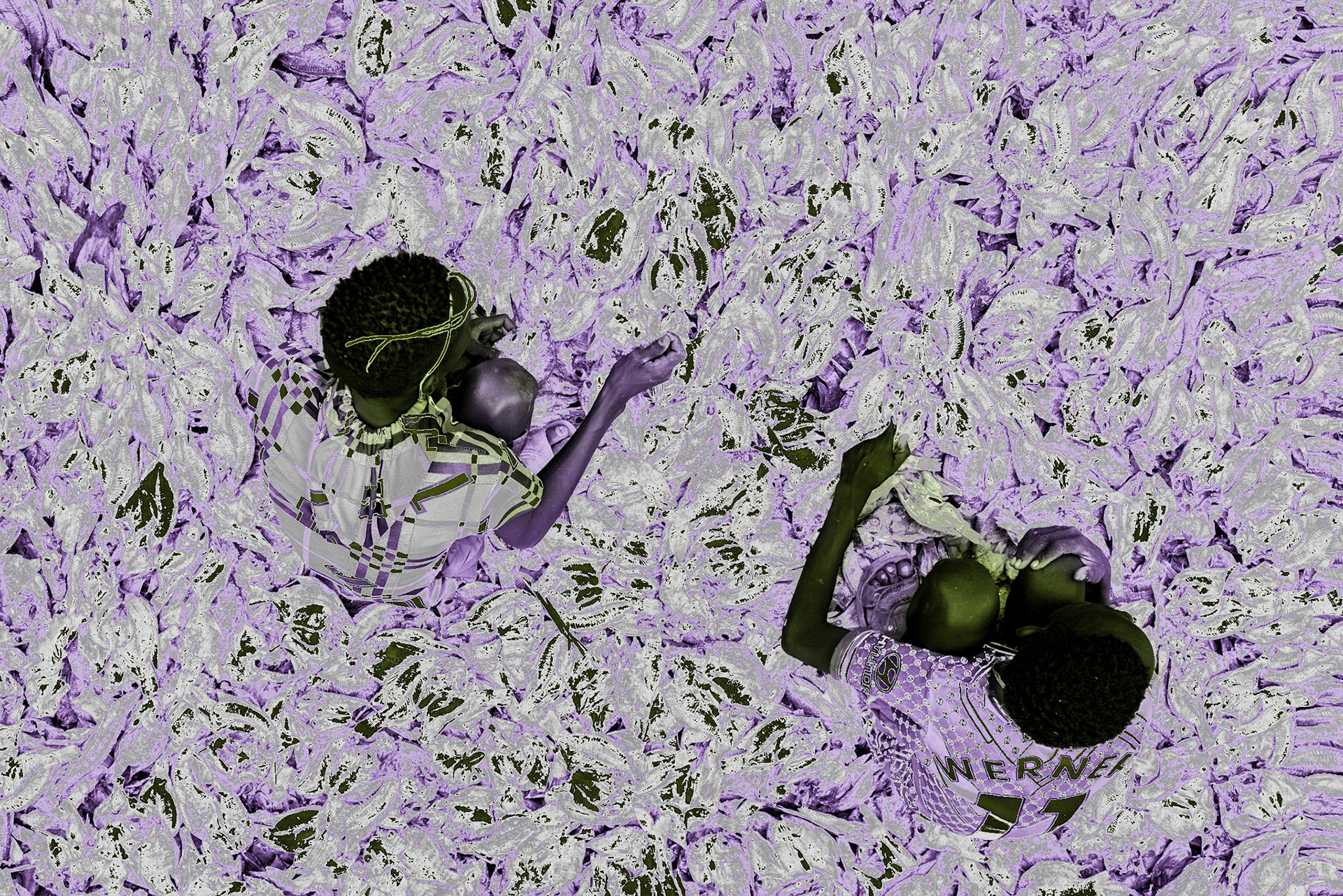

In Selicho, two Daasanach boys are working on a truck filled with dried fish. They are employed by Somali businessmen. The process of filling a truck with fish takes three days. The fishermen sell the fish for 30 Kenyan shillings per piece, but Somali buyers later resell the fish in Busia for 150 Kenyan shillings per piece. A 10-wheel truck can hold around 100,000 fish, weighing more than 20 tons.

A man sits on the roof of a truck loaded with dried fish from Lake Turkana. The war in Ukraine has caused a spike in fuel prices in Kenya, which is why the truck is carrying two barrels of diesel from Ethiopia. To avoid the police, the truck also drives without lights during the night after the curfew imposed due to a tribal conflict.

Two Somali men are praying on the road from Selicho to Marsabit, a journey that takes around 20 hours through the desert. They are driving a truck loaded with dried fish and travelling up to Busia at the border of Kenya and Uganda. There, the fish will be sold for the final destination market, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A pickup track is carrying an injured camel in Marsabit county. The camel was stolen by 12 armed bandits two days earlier in Karare. Later that day, there was a vehicle attack in the same area which resulted in six deaths and 11 injuries. After being stolen, the camel eventually escaped and returned home.